Let's Explore: Early AGP Cards

Introduction

In the mid-90s, the gaming performance bottleneck had shifted from being the CPU to sluggish graphics processing, due in large part to the rise and ever-growing popularity of 3D games. This upcoming challenge probably first hit home around 1993, when games like Doom, Indycar Racing and Tornado arrived on the scene, requiring a high-end PC with the latest CPU and a large amount of main memory. VESA, the video standards body, came out with their 32-bit VESA Local Bus design that year, with supporting graphics cards able to communicate directly with the CPU at 33 MHz, vastly quicker than the legacy ISA bus's 8-10 MHz. This was, however, pretty shortlived as it was really rather locked down to work with the 486 microprocessor.

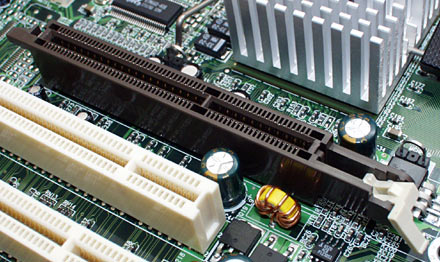

An early AGP 1x slot (1997)

Intel separately had been working on their own local bus standard since 1990 with the platform-independent PCI (Peripheral Component Interconnect) bus, and this launched along with the first Pentium processors in 1994. Not only was PCI also able to communicate with the CPU directly at 33 MHz, it could do so using a 64-bit wide data path. Within a year, VLB was dead, superceded by the more flexible PCI bus standard and future proof.

Accelerate forward to 1996 and the limitations of the PCI bus were showing. It wasn't optimised for pushing huge amounts of graphics instructions between the CPU and graphics card. It was a bus whose data lines had to be shared by multiple devices, and as such compromised the much-needed performance demand of the graphics card if more than one device was trying to get time with the CPU. Soon after its inception, the PCI bus standard was updated several times to support higher bandwidths, but by 1997 it was creaking - for all other peripherals it worked great and had become the universally-supported bus type for all expansion cards, but the graphics accelerator freight train hasn't slowed - demand for faster graphics throughput was unyielding.

Enter the Accelerated Graphics Port, or AGP, designed by Intel in 1996 and arriving in the Socket 7 and Slot 1 platform in 1997. For the first time, we had a dedicated port for the graphics card able to communicate directly with the CPU at 66 MHz - twice the speed of the original PCI standard.

Early Support

Motherboard chipset manufacturers jumped on AGP as soon as they could. The first to do so were VIA with the Apollo VP3, ALi (Acer Labs Inc) with their Aladdin V, and SiS with the 5591/5592. While these all fully implemented the AGP specification, the same could not always be said for the graphics card manufacturers. In a rush to get AGP cards on the market, some of the earliest cards were just modified versions of their existing PCI cards with a PCI-to-AGP bridge onboard. This was entirely possible because AGP wasn't really a new standard - it was an extension of the PCI 2.1 specification. Without using any of the AGP-specific features, the AGP slot operated just like a 66 MHz PCI slot.

On some of the earliest cards, very few of the bells and whistles made possible with the AGP standard were implemented (though they did benefit from running at the faster 66 MHz bus speed). Here's what I believe were the first AGP cards to hit the market (many manufacturers made hasty announcements of their forthcoming offerings as early as late 1996):

- February 1997 - Cirrus Logic Laguna3D-AGP (CL-GD5465 graphics processor)

- March 1997 - ATi 3D Rage Pro

- March 1997 - Trident 3DImage 975 (3DImage 9750 GPU)

- May 1997 - 3D Labs Permedia 2 (GLiNT Gamma)

- August 1997 - Diamond Fire GL 1000 Pro

- August 1997 - Number Nine Revolution 3D (Ticket to Ride)

- August 1997 - S3 ViRGE/GX2

- November 1997 - Matrox Millennium II

- November 1997 - Oak Technology Warp 5

- December 1997 - Rendition Verite V2200

A key part of the AGP specification allowed for the use of system memory to store textures (the "AGP Aperture"). One of the reasons for this was that dedicated fast graphics memory was still expensive, so allowing system memory to double up as texture storage memory was a decent stop gap until graphics memory prices came down. It also meant graphics chipset manufacturers could offer motherboard-embedded versions of their chips with no dedicated graphics memory required. This was known as AGP texturing. AGP provides two distinct modes of operation - DMA mode, which only uses local texturing in the frame buffer, and large textures held in system memory are transferred via a DMA operation to the local frame buffer ready to be processed by the GPU. Execute mode allows the accelerator to use both system memory and local frame buffer memory and store certain types of data in each based on their size for optimal performance.

One feature omitted on some early AGP cards is sideband addressing (SBA) - a way of making more efficient use of the bus through the simultaneous sending/receiving of commands and data.

Some early motherboards that supported AGP had issues with later AGP cards, even if they were electrically compatible. This was due to the current demand of higher-end cards - it's not a failure of the specification, but of the motherboard's design.

Now let's take a look at some of these early AGP cards...

Cirrus Logic Laguna 3D-AGP

Probably the very first AGP chipset and card released to manufacturing was the Cirrus Logic Laguna 3D-AGP. Based on an updated version of their popular CL-GD5464 graphics chipset called CL-GD5465, this continued to use RDRAM memory from Rambus, which was supposedly up to ten times faster than typical DRAM of the time. With the 5465, the speed of this memory rose from 500 MHz to 600 MHz. The chipset supported from 2 to 8 MB of local graphics memory, though only 2 and 4 MB versions were eventually produced.

Cirrus Logic Laguna 3D-AGP (Feb 1997)

Unfortunately, the 3D graphics core was a bit buggy, with poor perspective correction, heavy dithering in 16-bit colour modes, a complete absence of fogging (despite its spec sheet having this), only a 1 KB texture cache onboard, and a poor implementation of bilinear texture filtering. There were also some issues with games not running properly due to textures existing in system memory, not local memory. The AGP card's performance however, was pretty decent - up there with the later ATi Rage IIc AGP.

ATi 3D Rage Pro

I've covered the 3D Rage Pro in a more dedicated article here, but to summarise, its Rage III core improved on its Rage II forebear, now fully supporting the AGP v1.0 standard with 133 MHz pipelining (on 3D Rage Pro AGP 2x cards) when executing from system memory. The chipset featured new triangle creation which took the strain of doing this task off the CPU, perspective errors of the Rage II were gone, and its texturing engine now had 4 KB of cache.

The cards typically ran with a core clock speed of 75 MHz with memory at the same speed, offering bandwidth of up to 600 MB/sec. Later versions of the card increased the memory clock to 100 MHz (800 MB/sec bandwidth).

Overall, a solid card and graphics core with an excellent 3D feature set that works.

Trident 3DImage 9750

Known for its low-cost OEM video cards, Trident were quick to launched an AGP card based on its 3DImage 975 3D graphics accelerator. They called this 3D graphics processor rCADE3D, and featured bilinear filtered texturing, perspective correction, Gouraud and flat shading, 16-bit Z-buffering and OpenGL-compliant blending. The chip came with a feature-rich 2D 24-bit colour accelerator and a 170 MHz RAMDAC. According to the spec sheet it could render a sustained 1.2 million polygons per second and a peak fillrate of 66 Mpixels/second. It also supported 2 to 4 MB of SGRAM running at 83 or 100 MHz, though these cards came with standard EDO DRAM running at 55 MHz.

Trident 3DImage 975 (March 1997)

Sadly, their spec sheet failed to mention the performance numbers were at the lowest 8-bit colour depth - raise it to 16-bit, and you could expect closer to 600,000 polygons per second, which was not earth shattering. It also suffered from broken textures and poor perspective correction. Typical performance was similar to an S3 ViRGE/DX with the same memory. Like the Cirrus Logic, this one is best avoided.

3D Labs Permedia 2

Unlike some other cards in this pack, the Permedia 2's Texas Instruments GPU (TVP4020) does support the full suite of AGP 1x features, including sideband addressing, but because it's AGP 1x, it only supports a 66 MHz bus. The chip also came with a fast embedded 230 MHz RAMDAC.

Creative Labs 3D Blaster Exxtreme with Permedia 2 GPU

The card was not only fast, but had good texturing, bilinear and trilinear filtering, alpha blending, vertex shading, and Z-buffering, all at a 16-bit colour depth. 3D Labs always favoured OpenGL over DirectX, since its history was more in the professional graphics market, and this shows in somewhat buggy drivers for DirectX.

Diamond Fire GL 1000 Pro

The Fire GL 1000 Pro used the same 3DLabs Permedia 2 chip as the Creative card above, so it's a similar story. Reviews at the time indicated that actually the Direct3D drivers were decent (as well as the OpenGL ones).

Diamond Fire GL 1000 Pro with Permedia 2 GPU

Overall, the card benchmarked very well, though reviewers cautioned that a high-end CPU was also really needed to get the most out of it. A top card if you can get one.

Number Nine Revolution 3D

The Revolution 3D was Number Nine's flagship product, winning many industry awards including being the "Editor's Choice Award Winner" by both PC Magazine and Byte Magazine. Using its "Ticket to Ride" core, it supported both Direct3D™ and OpenGL® 3D acceleration with its 128-bit 3D engine and pushed 650-MFLOPS (million floating point operations per second) for some solid PC gaming performance.

Number Nine Revolution 3D (August 1997)

Earlier versions of the card used WRAM, but in early 1998 SGRAM versions arrived. The Ticket to Tide chip had a whopping 8 KB texture cache and a 220 MHz RAMDAC. Its 3D capabilities were decent too - specular lighting, interpolated fogging, alpha blending, bilinear texture filtering, and more.

Unfortunately in my tests, poor or completely missing texture filtering was prevalent in a lot of games. I'm sure a lot comes down to the drivers, as was so often the case around this time. Generally, the Revolution 3D was considered an excellent card at the time, offering excellent performance and quality.

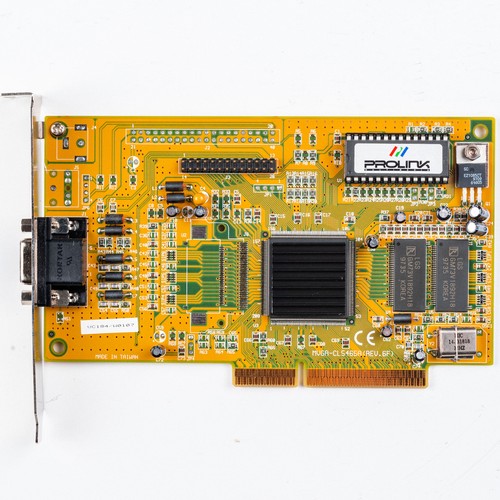

S3 ViRGE/GX2

The ViRGE/GX2, also known by its codename 86C356, was S3's first AGP graphics accelerator chip, with all four of the earlier ViRGE family being on the PCI bus. At the time of its release, S3 had already sunk a fair bit in the market, producing low-end (and more importantly, low-performance) graphics chipsets compared to the rising competition. Cards based on these all had excellent 2D image quality and performance, but the 3D engine was consistently a letdown, despite being very full-featured. The memory bandwidth on the GX2's SDRAM or SGRAM architecture was an improvement over the earlier chips, with up to 720 MB/s memory bandwidth, compared to 400-600 MB/s on the earlier ViRGE series chips.

A card featuring the S3 ViRGE/GX2 GPU (August 1997)

The GX2 offered little in the way of features supported by the new AGP bus, however. Couple that with lacklustre performance compared to the competition, and it didn't win our hearts. A real shame, as the 3D feature set was excellent, and the 2D core was rock solid.

Matrox Millennium II

Ah, Matrox - always considered the gold standard in 2D image quality due to their long history producing professional-grade graphics cards. I've covered the Millennium II in detail in a more dedicated article here, but suffice it to say the card righted the wrongs of the original Millennium, with 3D capabilities more in line with expectation in late 1997. Millennium II's new MGA-2164W processor had a more powerful 3D Gouraud shading engine than the Millennium's MGA-2064W, support for a 32-bit Z buffer, up to 16MB of fast dual ported WRAM and hardware accelerated perspective correct texture mapping.

Matrox MGA Millennium II (November 1997)

The new core was taken from their Mystique, and so unfortunately it still lacked bilinear fexture filtering - a key 'miss', and reviews at the time were damaging - mostly due to the card's very poor 3D performance, poor rendering quality and overall lack of support for many Direct3D modes. So despite supporting the highest resolutions of any card in this group, and offering the best 2D quality (and probably performance too), this one falls down the rankings badly.

Oak Technology WARP 5

Oak Technology jumped on the AGP bandwagon in late 1997 with their Windows Accelerator and Rendering Processor (WARP) 5 graphics accelerator, also known by its codename OTI-64317. Unlike other GPU makers, Oak implemented a region-based architecture for 3D, which split the screen display into regions for processing, which apparently would reduce memory bandwidth issues.

The 3D core was pretty full-featured, offering perspective corrected trilinear MIP-map textured, anti-aliased, Z-buffered, Gouraud shaded, and fogged polygons, and advanced texture techniques included trilinear MIP-mapped filtering, perspective correction, subpixel full-scene anti-aliasing, and a memory-less 24-bit floating point Z-buffer.

Also onboard was a decent 2D accelerator and a 175 MHz RAMDAC. Cards used up to 8 MB of single-cycle EDO DRAM.

Performance-wise, they touted 50 million pixels/sec processing. This all sounds impressive - unfortunately, I don't have any further information or evidence of how these cards worked in the real world. If you have experience of a WARP 5 card, let me know! I believe it was actually a cancelled project, as this was to be Oak's final graphics chip.

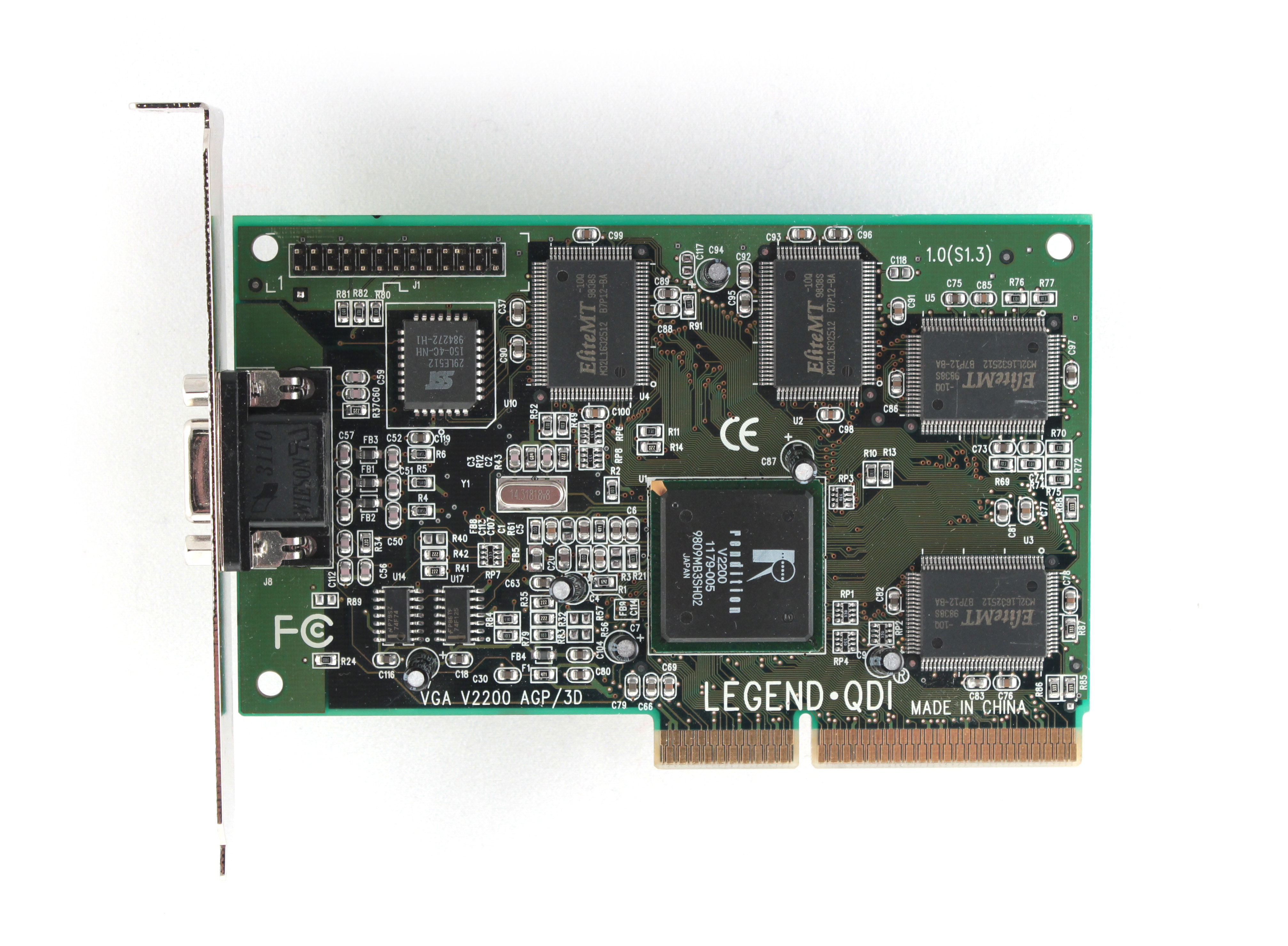

Rendition Verite V2200

The Verite V2200 was the faster of the two new Verite 2 graphics accelerators, with this one coming with an integrated 220 MHz RAMDAC (the V2100 got a slightly slower 200 MHz one). Unfortunately, this was one such card that was only electrically compatible with AGP, but internally it was all PCI - having said that, it was able to run at 66 MHz. One thing that differentiated the Verite V2x00 series from others was the use of an onboard RISC CPU for faster instruction queueing and processing. A new triangle engine allowed for single-pass processing, and with a full 3D feature set including specular highlighting, bilinear texture filtering, z-buffer, fog and alpha blending, all able to process at one cycle per pixel, and it should have been a winner. One key 'miss' in the 3D engine was a lack of per-pixel mip-mapping - only per-polygon was supported.

A Rendition Verite V2200 card (December 1997)

Sadly this chip was let down by slightly buggy drivers in OpenGL and DirectX, resulting in patchy rendering and alpha blending often missing completely.

Performance-wise, it held its own, but like so many cards in this review it was let down by driver difficulties.

Conclusion

So there we have it. 10 of the very first 3D graphics accelerator cards and chipsets on the AGP bus. There are some good ones, and others that should be given a very wide berth. Whenever new technology and standards come along, the first offerings are bound to be hit and miss, and early adopters face the risk of being stung.

It should be said that DirectX 5 was brand new in August of this year, so even if hardware drivers were implemented correctly to support certain features, there's a high chance the games themselves also released with bugs that failed to work correctly as per these features, or were sub-optimal in performance. As we moved into 1998, AGP became better understood and drivers stabilised, resulting in more consistently reliable cards to use with games that year.

Out of this bunch, if you're looking for an early AGP card, I would probably go for the ATI 3D Rage Pro or Diamond Fire GL 1000 Pro, due to more solid driver support and decent performance. If you had any of these cards or chipsets and have some feedback, do get in touch via the "Contact Us" link below!

.png)